One of the joys of teaching mindfulness is that I make new friends through the people who come on my courses or to the class. These friends initially come to learn mindfulness and I am in the role of a teacher, but as they then establish their own practice they become fellow practitioners and can often end up teaching me, inspiring me as they share their experience. This happens with a number of people, but a few weeks ago I received a text that was beautiful in its succinct expression of the power of mindful enquiry.

The person who sent this had initially come on an 8 week mindfulness course I ran a few years ago. They found it very hard at first to connect with the body scan and to notice any sensation in their body. But they kept going, slowly opening to noticing the sensations they had spent so long being cutting off from. There were times when this meant feeling a lot of things they had not wanted to feel, but over time it has become a gift.

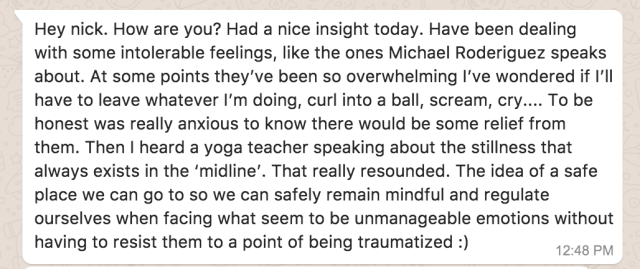

I had sent them a link to a teacher I am currently interested in, called Micheal Rodriguez, who spoke of being with difficult feelings in the body and how we want to run away from them, but in turning to feel them we can find a freedom that is blissful. In response he sent me this text. In subsequent conversations I asked if it was ok to share it as it has a few things in that I found very moving.

This is something I have been hearing from different teachers recently, the emphasis on trusting that within the chaos of experience there is a stillness that is always accessible. When I visited my old monastery last year and met with the Abbot there, he spoke of how mindfulness is a practice for building a container that can hold the chaos, enabling us to be present with our struggles without being overwhelmed.

There’s a Tibetan saying about meditation: “better not to start, having started better not to stop”. What this refers to is that as we learn to meditate we open to so much that we once were oblivious to. It may feel at first that things are getting worse rather than better, as we feel more deeply into all of the things we had pushed away into the shadow of denial. Having started this process if we stop then we are simply stuck in a place of feeling more without any release from this deep intensity. As we continue with this mindful enquiry though we can start to sense that we are not just the chaos, instead we start to wake up to the witness.

In the Thai Forest tradition in which I trained, they refer to ‘the one who knows’. This is the wisdom that arises as we practice mindfulness. It is the mind’s ability to know all that arises as a creation and to know not to believe the stories the mind weaves about things. It is the wisdom that can hear an unpleasant sound and instead of going into thoughts of dislike and disgruntlement, simply knows it as a sound, with certain qualities of tone, pitch and volume. Or someone can say something hurtful to us and it is known for what it is: an opinion from another that we give life to by either liking what they say or disliking it.

Our suffering starts when we pick up what they offer, start identifying with it, believing that we are as bad as they say, or getting angry with them because we feel they are disrespecting us. If we leave it for them to hold, then, to summarise a metaphor the Buddha used, it is like an unwanted present we choose not to accept. As we listen quietly like this to our reaction to what they say, to their words and how they are being, we may even pick up a sense of their words coming from a place of pain or suffering – envy, anger or resentment. If we hear this then our potential anger may turn into compassion for them.

Our minds are meaning making machines – we look for meaning and weave stories around what we see, hear and sense. The ‘one that knows’, the wisdom of stillness, knows not to buy into that drama. Instead it notices with a calm attention, sensing how our response to something is starting to create eddies in the mind – little ripples of attraction or aversion that in a few moments can become crashing waves of elation or despair.

Ajahn Chah would always teach that mindfulness is the way to connect with ‘the one that knows’ – the state of mindful and non-reactive Awareness that we connect with when looking with a calm and clear attention at any sensory experience that arise in our body-mind: thoughts and bodily sensations. As my friend did this, they first noticed the intensity of emotions in their body. As Ajahn Chah has said of meditation, “unless you have cried deeply you have not even started to meditate”, Awareness will open us to the fear, the pain, the trauma we have for so long denied. But as Ajahn Chah also says of meditation: “when you sit, let it be, when you walk, let it be, grasp at nothing, resist nothing”. The state of knowing, ‘the one that knows’ arises as we turn with calm presence to our experience right now – neither trying to push it away, nor deny it or make it otherwise to what it is.

Ajahn Sumedho, my teacher from the monastery who trained under Ajahan Chah in Thailand, puts it like this:

“In the moment of mindfulness, there is no suffering. I can’t find any suffering in mindfulness; it’s impossible; there’s absolutely none. But when there’s heedlessness, there is a lot of suffering in my mind. If I give in to grasping things, to wanting things, to following emotions or doubts and worries and being caught up in things like that—then there is suffering. It all begins from my grasping. But when there is mindfulness and right understanding, then I can’t find any suffering at all in this moment, now.”

In the text above, my friend felt into the intensity of the experience that was presenting itself in that moment, knew it, and trusted that there was a stillness that was not the difficult emotions or painful sensations. In that moment the ‘one that knows’ arose and there was a clear seeing and suffering came to an end, at least for a few seconds! These little insights at first seem insignificant, but the wise people I was so lucky to live with in the monastery were examples of how with persistent and committed practice there can be a shift – from these being brief glimpse of insight, to living from this as an ongoing experience.

If you would like to explore this further, the full text of Ajhan Chah’s talk is here, and the full text of Ajhan Sumedo’s talk is here. The video I mentioned at the start of the email is below.